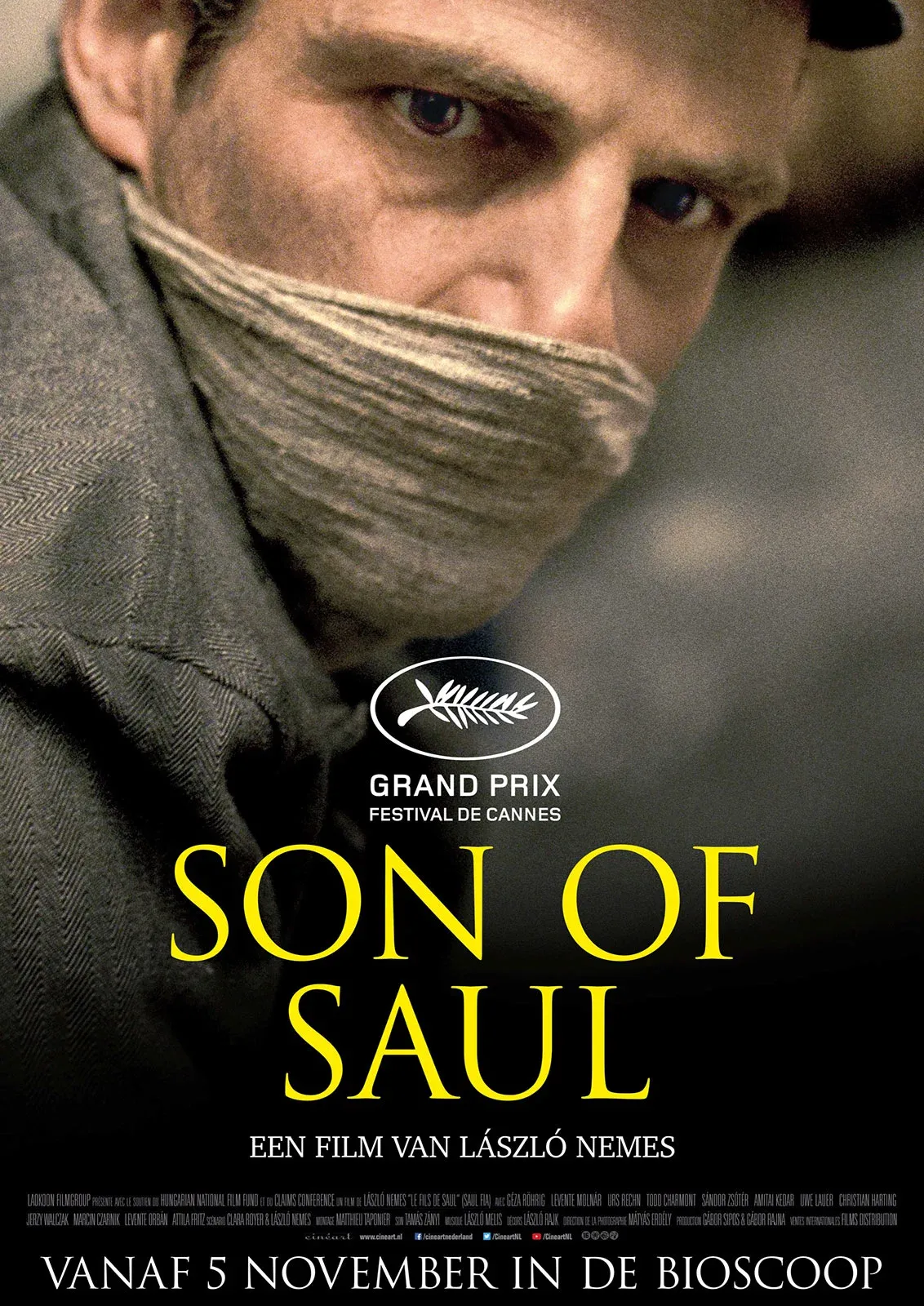

Son of Saul : How László Nemes Differentiates from other movies depicting the Holocaust.

- Dune Stewart

- Mar 21, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2020

Son of Saul’s gripping storytelling through the sensory imagery it presents as a substitution to its lack of facial expressions, creates a unique perspective on the numerously touched upon subject, The Holocaust. Blending a fictitious story of madness as our main character, Saul, dodging attempts at being caught for the sake of spiritually saving a boy who initially survived a gas chamber execution, finds himself in the midst of historical events that combat his moral intentions, before what he believes will be his imminent death. The blurred background imagery, with the foreground following Saul’s point of view throughout the entire course of the film, really embodies the idea of dissociation as a Sonderkommando when an individual has been put in that role for an extended period of time. As described by László Nemes, the director, this is a story “not about physical survival, but inner survival.” Saul takes upon a quest for the fight of morality throughout the duration of the film, where the possibility of rebellion ceases to be an obstacle of moral dilemma, putting those in the present, above the spiritual needs of the deceased.

As the audience follows Saul, the camera is mainly behind him to have us perform the duties of a spectator in “hell.” A red x marks the back of his jacket to indicate his placement as a Sonderkommando, but I find that as he continues to pursue his goal, it can be seen as a target indicator for his enemies, and that Saul needs to be watching his back, so he doesn’t get caught. The camera does interchange the angle, but during Saul’s movement frames, we mostly see his jacket, then we do his face, and it is as if the audience is playing the role of protector over the man whom wishes to do something good in a world of horror. A specific scene that draws more attention is when Saul is with another prisoner whom is taking photographs to send out to the resistance, and Saul steps out of the shed into a cloud of smoke that fills the landscape, and we can still see the x marked on his back, which I believe is a foreshadow to the ending sequence. With the cinematography focusing in the foreground and blurring the background, it is familial object formations and sounds that overtake our senses for what surrounds Saul as he traverses across the camp. As one interviewer stated, they were “the sounds of hell,” and I think that only furthers the engagement and the reasoning to support the decision of shallow depth of field throughout the film. Allowing for this type of camera movement, it shared a more personal experience held by Saul, and reinforced the nature of dissociation by choosing to focus on the automative functions given to humans by their job performances. Nemes described his approach as a way for distant generations to connect with an unfamiliar event, since they are not actualizing it from a place of fear or trauma, but from a place of understanding what happened. Many article writers declared that it’d be impossible to replicate or explain the horrific events of the Holocaust, because “things were always evolving,” and any story that comes out of it, will only be fragmented against its actuality.

In contrast to this assumption, I think the argument can be far negated by the director’s decision to base upon his historical context from “The Scrolls at Auschwitz” (which were written by prisoners in concentration camps), and additionally had historical researchers implement additions that they felt would add to the credibility of the film’s context. Although, I can agree that a fictionalized narrative feature film will only stretch the truth so far, when compared to a documentary from modern day testimonials, it still deserves more recognition for its attempt to recreate more precise circumstances regarding the concentration camp lifestyle. Even the plot’s fictional aspect itself is implemented into historical context, when Nemes stated that the story of the child came from his head, but it was reinforced when his historical advisor let him know that of the 430,000 Hungarian deportees, 100,000 of them were children.

Given the thematic nature of moral superiority surrounding the child, and the fight for inner survival, it is the philosophy of free will/free choice that comes into question. The idea of whether or not it is his child, is not of importance, but of why it took precedence? It was said by Nemes, that this “madness was a form of inner revolt,” that allowed for a statement within his control, knowing he would die at some point in the camp. Under the action of automation, is it possible that his dissociation, made it irrational for him to challenge the systematic principles onset by the Nazis, and it wasn’t until he saw an opportunity, that his ability to use free will was accessible? Is free will always available, even when not present in the moment? Some critics wish to identify Saul as an accomplice to the massacre of concentration camps given his role as a Sonderkommando, but is free will accessible when a gun is pointed at your head, literally?

Lubuza, a film critic from LA, found the film to be lacking intellectualism regarding the historical context of the Holocaust, and mainly chose to avoid the horror that it represents. I disagree with Lubuza, and agree more with the argument demonstrated by Richard Porton, because the intellectualism could not be fairly judged given that it was hardly even talked about as a main subject. The movie was not created to mirror Holocaust imagery that would garner more attention to the associations that the public already has amassed since its occurrence, but rather tell a compelling narrative piece for a specific individual that was placed within that situation. Lubuza’s concept of Nemes disregarding the horror, is absurd, because it is through blurry movement and shallow depth of field, which brings more attention to the background elements, even when they are not given literal grotesque representation. If anything, I would assume the audience would approve of a much more nuanced position to the violence and horror associated with Auschwitz, because its events are already globally known and researched. It is now a time for specific storytelling that will depart from the usual perspective of retelling the Holocaust. Son of Saul is nothing but brilliant, and I am excited to see what’s next from László Nemes.

Comments